Structuring Your Giving Part 3: Choosing the Best Structural Form(s)

Jul 13, 2022Figuring Out Which Giving Structures Make the Most Sense for You, Part 3

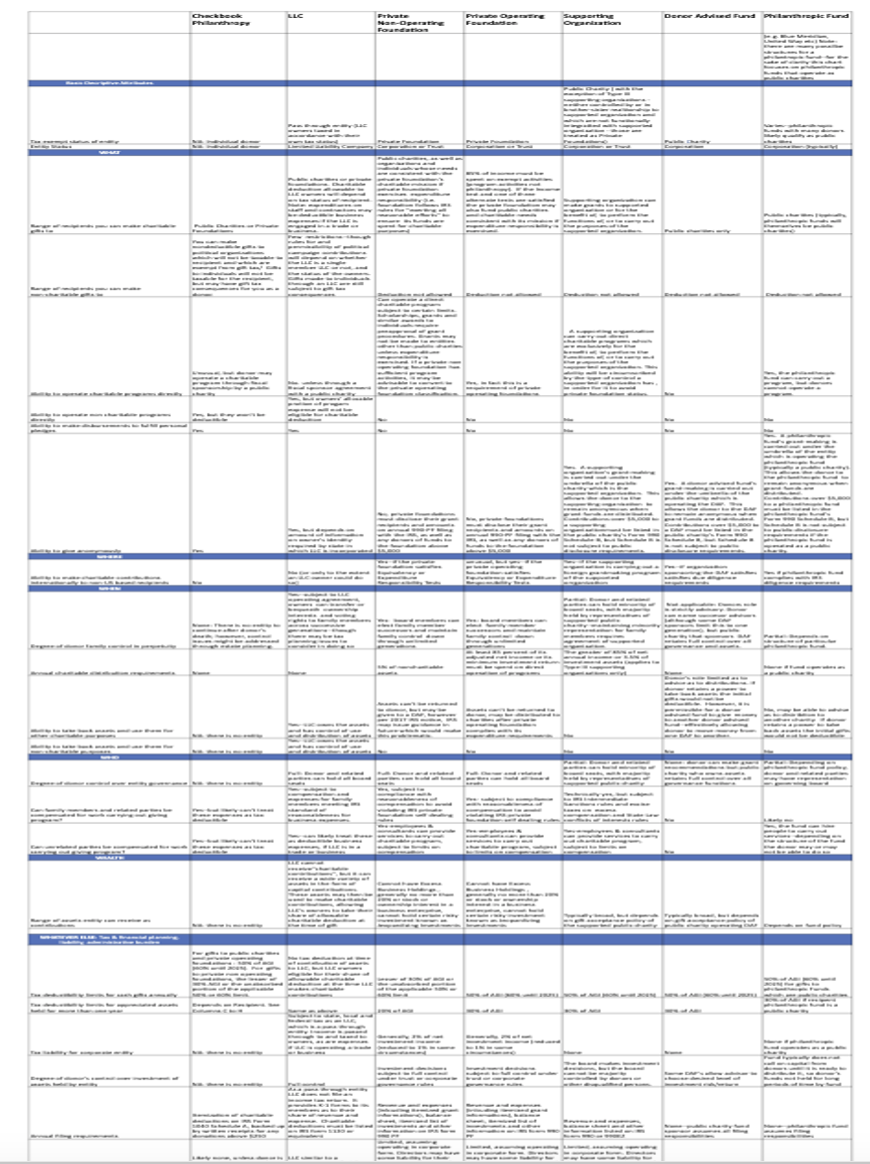

As we began to explore in a previous post on this topic, there’s a lot to consider as you try to figure out which giving structures are the best match for carrying out your giving. Here’s what I recommend: begin by identifying which of the key functional questions (what, where, when, who, wealth stock and whatever else) reviewed in this post and the previous post are most relevant to your giving. Then consult the corresponding sections of this summary chart to see which of the 7 structural forms (checkbook philanthropy, donor advised fund, private foundation etc) are the best fit.

You can download a full size version of this table here.

You’ll still need to do your diligence and consult your financial and legal advisors before making your own decisions, but this chart is great for getting the big picture with a side by side view of the different features and attributes for the 7 main structural options for your giving:

- Checkbook philanthropy

- LLC

- Private non-operating foundation

- Private operating foundation

- Supporting Organization

- Donor-Advised Fund

- Philanthropic Fund

In an earlier post in this series, we looked at the key functional questions of What, Where and When. In this post we'll conclude the process of walking through this chart by looking at key functional questions of who, wealth stock and whatever else.

Key Functional Questions Part 2

WHO—Who is involved in distributing your giving?

Degree of donor control over an entity’s governance

How much legal and practical control do you want to have over the governance of the entity in which you place your funds? The seven options we are reviewing here differ considerably regarding the extent to which you and your family members (or other, related parties) can play a controlling role in governance. At one end of the spectrum, checkbook philanthropy and the solely owned LLC assure the donor the greatest degree of control. At the other end of the spectrum are donor-advised funds. In this case, you are giving up legal and operational control in favor of the public charity to which you have given your funds. Although you do have the opportunity to make recommendations about grants to make with these funds, the DAF is under no legal obligation to follow your requests. In reality, the marketplace for DAFs is highly competitive. It is extremely unusual for a DAF not to honor such requests, provided the intended recipients are public charities in good standing. Private foundations, including both non-operating and operating varieties, show up much closer to the donor control side of the spectrum. You can form and operate these private foundations with no one other than you and your family members involved in their governance. As a consequence of this much donor control, private foundations face more restrictions and regulatory requirements than some of the other philanthropic vehicles. Other options, such as supporting organizations, sit in the middle of the donor control spectrum by providing the donor the opportunity to be represented on the governing board on a minority basis. In this case, the supported public charity takes the majority of seats. In practical terms, however, some donors have worked with donor-friendly, public charities like community foundations to create supporting organizations. These can afford the donor a great deal of operational control on a day-to-day basis.

Compensation for family members and related parties

Do you want to be able to pay family members, business associates, and other related parties for serving on your board or for serving as staff? If so, you’ll need to consider this as you structure your approach. Private foundations allow for this, meaning you can use dollars for which you have received a charitable tax deduction to pay family members and related parties a “reasonable” amount to compensate them for services rendered in governance or staffing roles. You can also compensate family members and related parties for services rendered to an LLC and, subject to some restrictions, treat these as deductible business expenses. Some other structures, such as DAFs, do not allow any compensation of family members or related parties.

Range of unrelated parties you can compensate for services rendered

If you expect to hire staff or consultants to help you carry out your giving, this is an important issue to consider. For example, if you vest all the resources you intend to use within a donor advised fund, then decide you want to hire some help, you cannot use any resources from your donor-advised fund to pay for these staffing costs. This would leave you having to pay for staffing from your personal funds. But, if you also have a private foundation or an LLC operating alongside your donor-advised fund, you may be able to treat staffing costs as the deductible operating expenses of these other entities.

WEALTH STOCK—What forms of wealth do you plan to deploy in your giving?

Different Assets You Can Give to an Entity

If you have complex assets like artwork, real estate, or shares in closely held, private companies that you want to use as the basis for your giving, then you’ll need to consider what types of entities are able to receive or hold these assets. One important consideration is that private foundations cannot hold more than a 20% interest in any one company. This is one reason why Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan set up an LLC instead of a private foundation when they pledged to give away 99% of their majority interest of Facebook shares. This is definitely an area where you will want to seek expert guidance based on the assets you have in mind. For example, if you plan to donate complex assets to a donor-advised fund or philanthropic fund, you’ll want to check in advance with the administrators of those entities regarding what range of assets they are equipped to accept or hold.

Another thing to consider is whether you plan to base your philanthropy on your own individual, intellectual, or social capital. If so, does this mean that you plan to run programs directly? Do you want to? As discussed under the “WHAT” section above, if you want to run programs directly, you may want to consider an LLC or private operating foundation to maximize your sense of involvement and fulfillment.

WHATEVER ELSE—Taxes, financial planning, administrative burden, legal liability, and more

Annual Tax Deductibility Limits for Cash Gifts

The key distinction to track here is how much of your adjusted gross income (AGI) you can treat as a tax-deductible contribution to a giving vehicle each year. The limits vary and are subject to adjustment as policies change. In general, you can contribute 50-60% of your AGI in cash on a tax-deductible basis to a donor advised fund. Conversely, the tax-deductible contribution limit for cash gifts to a private foundation is only 30% of your AGI in any given year. You may want to consider these limits when looking at your philanthropic structure if you are planning to make relatively large gifts as a percentage of your AGI each year.

Annual Tax Deductibility Limits for Appreciated Assets

This is an issue if you want to donate appreciated securities, real estate, or other assets on which you have accumulated capital gains. Again, the tax deductibility limits vary from one vehicle to the next, but in general, private foundations have a lower limit (20% of AGI) than do donor advised funds (30% of AGI).

Tax Liability on Investment Earnings for Corporate Entities

Does it matter to you whether the entity you use to carry out your giving has ongoing tax obligations on income earned from its investments? This comes up particularly for private foundations, as they are generally liable to pay 2% of their net investment income in taxes on an annual basis. By contrast, donor-advised funds and supporting organizations operate as public charities. This means they are not generally subject to any tax obligation for earnings on investment income. This distinction is one reason why some high-capacity donors who intend to actively manage their philanthropic resources for maximum investment return have created supporting organizations as the vehicle for doing so.

Degree of Donor Control Over Investment of Assets Held by Entities

If it’s important to you to be able to closely manage the investment of the assets that form the basis for your giving, you’ll want to consider this as you structure your giving. Generally speaking, the more closely you control the governance and operations of the entity, the more control you’ll likely be able to have over the investment of its assets. This may be particularly important for donors who are investment professionals. There are certainly instances of private foundations whose investment performance dramatically outperforms the market due to the active engagement of the founder or other investment professionals serving on the board. The Lynch Foundation, for instance, unquestionably achieves better returns by having Peter Lynch run its investment portfolio than it would parking its money in a typical mutual fund. That said, this isn’t a decisive issue for many donors when making choices about how to structure their giving. Even donor-advised funds typically offer donors the opportunity to choose investment options from an array of risk/return profiles.

Administrative Burden, Including Annual Filing Requirements

How much does minimizing administrative burden matter to you? Some entities have virtually no administrative requirements on you as the donor. For example, donor-advised funds are administered entirely by the public charity with whom the funds are vested. You can simply go online to see your fund balance, to make contributions, to adjust your investment allocations, and to make grant recommendations. At the other end of the spectrum, private foundations have annual filing requirements with the IRS and potentially also with state authorities. It’s worth noting that intermediaries like Foundation Source will handle most of the administrative requirements of running a private foundation for an annual fee, so you don’t necessarily have to hire your own accountants and bookkeepers directly.

Liability Exposure

It’s probably no surprise that your level of exposure to personal and/or organizational liability also varies considerably across the different giving structures. What kind of liability issues might come up in your giving? Good Samaritan laws provide some protection to individuals who engage in charitable activities in good faith when that activity somehow ends up resulting in injury or harm to others. Typically, the more control you have over the governance and operations, the more potential exposure you have to liability if something goes wrong. For example, if you establish a private foundation and serve on its board, you should carry director and officers’ insurance. This provides liability protection for you and other board members from claims based on alleged wrongful acts by the corporation. If you give funds to a public charity to operate a donor-advised fund on your behalf, you typically won’t have liability exposure. From a legal standpoint, you neither own nor control the resource in your donor advised fund—any liability risk is assumed by the public charity operating the fund. As with so many other areas of your life, it makes sense to assess the risks of legal liability and proceed accordingly based on your own risk profile and preferences.

Fiduciary Duty Exposure

If you’ve ever been involved with corporate boards of publicly traded companies, you may be familiar with the notion that board members have a fiduciary duty to place the interests of shareholders first. The issue of fiduciary duty arises in philanthropic giving around the question of who holds the legal responsibility to act as a steward of any assets you place into vehicles committed to charitable purposes. If you are operating as a checkbook philanthropist, the issue of fiduciary duty doesn’t arise. However, as soon as you receive a tax deduction for contributing funds to a separate legal entity, the public has an interest in ensuring that those funds are used to provide public benefit. In turn, whoever runs that entity may have a legal duty to ensure that the organization acts with appropriate care to steward those funds. As a cautionary tale, consider the court order that shut down the Donald J. Trump Foundation in 2019. Among the reasons for this action was that the organization had violated its fiduciary duty by using foundation funds to secure personal benefits for Donald Trump. One such expenditure was a six-foot tall, $20,000 portrait of Trump paid for by the Foundation and subsequently displayed in one of his golf properties.

A Final Word on Taxes

All too often donors get tied up in knots trying to maximize their tax advantages. This is not a path to truly meaningful giving—not for you and not for the world. Why not view the tax treatment of your giving as merely one among many operational considerations? In other words, do what you can to maximize the resources available by getting the benefit of charitable tax deductions, but only when doing so doesn’t distort your fundamental aims for impact or your sense of simplicity and personal fulfillment. After all, you are already planning to give this money away in pursuit of a better world. Why get hyper-focused on the intricacies of the tax code? If you wind up paying more taxes as you generate the greatest possible impact and personal joy, so be it!

Whatever design considerations are most important to you, none of them needs to be a barrier to gearing up your giving. Don’t fall into the trap of senseless giving by holding back until you have the perfect structure. Simply getting started is often the best way to learn which structures will really make the most sense for your philanthropy in the long run.

Stay connected with news and articles

Join us to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared, and you can unsubscribe at any time

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.